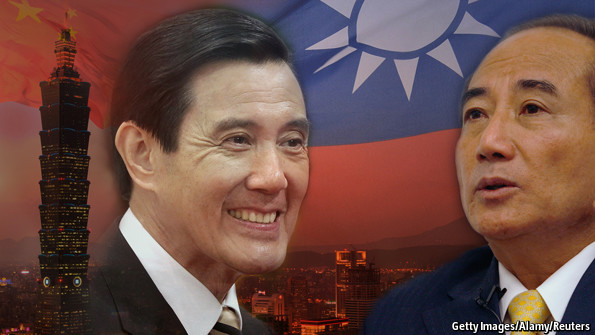

馬王之爭 牽動兩岸關係

在台灣過去17年的民主歷程中,幾乎沒有任何一位總統的民意支持度像馬英九一樣低。儘管常被眾人批評施政缺乏魄力,但如今卻因為決斷力而失去民意支持。這次處理王金平關說案的過程引發極大爭議,不僅威脅國民黨內部團結,更有可能因此影響兩岸關係。

就在檢察官指控王金平利用國會影響力進行司法關說後兩天,馬英九立即召開記者會表明立場:「關說案沒有和稀泥的空間。」根據檢察官說

法,王金平曾試圖說服法務部長曾勇夫,遊說檢察官在柯建銘涉嫌全民電通背信案由有罪改判無罪後,不要再提起上訴。馬英九表示,王金平關說案是「台灣民主法

治發展最恥辱的一天。」9月11日,國民黨正式宣布撤銷王金平黨籍。

台灣人民早已厭煩不斷爆發的政治弊案,因此按照常理來說,馬英九的行動 應該會得到多數民眾的掌聲。但是實完全相反,民眾普遍認為馬英九行為的真正的目的是為了剷除異己,而非維護司法獨立。此外,王金平一再強調自己的清白,再 加上身段柔軟以及出身台灣本土的政治形象(馬英九出生於香港,父母親均來自中國大陸),反而贏得藍綠兩黨政治人物的支持。9月13日,台北地方法院裁准王 金平的「假處分」申請,王金平得以繼續行使國民黨黨員權利,同時仍保有「立委」與「立法院長」資格。不同於法務部長曾勇夫在關說案爆發後以辭職明志,王金 平選擇了正面迎戰。

如今馬英九的處境頗為尷尬,立法議程掌控在他曾嚴厲譴責不適任立法院長的王金平手中。更糟的是,過去有多項法案,馬英九 希望可以藉由國民黨在立法院佔有多數的優勢強行通過,但王金平卻選擇與反對黨妥協,因而激怒了馬英九。但這次馬王之爭,不僅王金平不願屈從,其他國民黨大 老,包括榮譽主席連戰,也嚴詞批評馬英九的做法。這讓馬英九的處境更為不利。一位資深國民黨員表示,國民黨內幹部們的「普遍感受」是認為馬英九行動太過草 率倉促,沒有料到王金平有可能利用「假處分」扳回一城。

但馬王之間的鬥爭,絕對不能忽略中國因素。早在特偵組因為全民電通案監聽民進黨團總召柯建銘而意外發現王金平關說案之前,馬英九便對 王金平有所不滿。原本馬英九希望立法院可以儘速通過在6月時與中國大陸簽署的服貿協議,但立法院朝野協商後卻決定,服貿協議將採取逐條逐項審查、而非全案 通過的方式。政府高層擔憂若無法儘速通過服貿協議,日後與中國大陸之間的協商將更為困難。此外,這也會影響未來與其他貿易夥伴的經貿協商,一旦對方認為雙 邊協議有可能遭到立法院封殺,不可能願意與台灣進行自由貿易會談。

台灣人民早已厭煩不斷爆發的政治弊案,因此按照常理來說,馬英九的行動 應該會得到多數民眾的掌聲。但是實完全相反,民眾普遍認為馬英九行為的真正的目的是為了剷除異己,而非維護司法獨立。此外,王金平一再強調自己的清白,再 加上身段柔軟以及出身台灣本土的政治形象(馬英九出生於香港,父母親均來自中國大陸),反而贏得藍綠兩黨政治人物的支持。9月13日,台北地方法院裁准王 金平的「假處分」申請,王金平得以繼續行使國民黨黨員權利,同時仍保有「立委」與「立法院長」資格。不同於法務部長曾勇夫在關說案爆發後以辭職明志,王金 平選擇了正面迎戰。

如今馬英九的處境頗為尷尬,立法議程掌控在他曾嚴厲譴責不適任立法院長的王金平手中。更糟的是,過去有多項法案,馬英九 希望可以藉由國民黨在立法院佔有多數的優勢強行通過,但王金平卻選擇與反對黨妥協,因而激怒了馬英九。但這次馬王之爭,不僅王金平不願屈從,其他國民黨大 老,包括榮譽主席連戰,也嚴詞批評馬英九的做法。這讓馬英九的處境更為不利。一位資深國民黨員表示,國民黨內幹部們的「普遍感受」是認為馬英九行動太過草 率倉促,沒有料到王金平有可能利用「假處分」扳回一城。

但馬王之間的鬥爭,絕對不能忽略中國因素。早在特偵組因為全民電通案監聽民進黨團總召柯建銘而意外發現王金平關說案之前,馬英九便對 王金平有所不滿。原本馬英九希望立法院可以儘速通過在6月時與中國大陸簽署的服貿協議,但立法院朝野協商後卻決定,服貿協議將採取逐條逐項審查、而非全案 通過的方式。政府高層擔憂若無法儘速通過服貿協議,日後與中國大陸之間的協商將更為困難。此外,這也會影響未來與其他貿易夥伴的經貿協商,一旦對方認為雙 邊協議有可能遭到立法院封殺,不可能願意與台灣進行自由貿易會談。

民進黨立法委員向來對於任何與中國大陸之間的協議,抱持保留的態度。他們

擔憂中國大陸藉由加速與台灣之間的經貿整合,逼迫台灣進行統一談判。台灣政府高層則表示,服貿協議帶給台灣的好處將會大於中國。至於反對黨擔憂服貿協議將

會導致中國移民大量湧入台灣,並使得台灣中小企業無法與資本額龐大的國有企業進行公平的競爭,政府高層並未給予任何回應。

根據9月15日最新的民調,馬英九的民意支持度已跌至9.2%,創下歷史新低。現在有許多國民黨員擔心自己未來的選票,包括明年的縣市長選舉,以及2016年1月舉行的立法委員與總統大選,因此也不太願意為馬英九辯護。

就 在立法院決議逐條逐項審查服貿協議之後,中國方面曾表示疑慮,但是對於馬王之間的鬥爭,則不願發表任何評論。畢竟中國並不樂見國民黨的分裂,因為這將導致 民進黨再度執政,2000~2008年民進黨執政期間,兩岸關係陷入緊張,這讓中國引以為鑑。不過,即使仍由國民黨執政,未來兩岸的任何協議都有可能面臨 服貿協議相同的命運,至於政治上的協議或談判更是遙不可及。

但或許中國大陸已準備好接受民進黨重新執政的可能。去年10月民進黨前主席謝長廷率領黨籍立法委員與學者到大陸訪問,受到熱誠的接待,並與多位中國官員進行會談。

然而,這並不表示,中國大陸已經默許民進黨的台獨立場。中國大陸之所以釋出善意,或許只是想說服民進黨,中國並非如他們想像得會帶給台灣威脅。經濟部次長 卓士昭表示 ,中國方面完全了解,我們在立法院正和對於服貿協議有所疑慮的人努力奮戰。但是目前看來,身為這場戰爭總司令的馬英九,似乎沒有幫上什麼忙。(吳凱琳譯)

根據9月15日最新的民調,馬英九的民意支持度已跌至9.2%,創下歷史新低。現在有許多國民黨員擔心自己未來的選票,包括明年的縣市長選舉,以及2016年1月舉行的立法委員與總統大選,因此也不太願意為馬英九辯護。

就 在立法院決議逐條逐項審查服貿協議之後,中國方面曾表示疑慮,但是對於馬王之間的鬥爭,則不願發表任何評論。畢竟中國並不樂見國民黨的分裂,因為這將導致 民進黨再度執政,2000~2008年民進黨執政期間,兩岸關係陷入緊張,這讓中國引以為鑑。不過,即使仍由國民黨執政,未來兩岸的任何協議都有可能面臨 服貿協議相同的命運,至於政治上的協議或談判更是遙不可及。

但或許中國大陸已準備好接受民進黨重新執政的可能。去年10月民進黨前主席謝長廷率領黨籍立法委員與學者到大陸訪問,受到熱誠的接待,並與多位中國官員進行會談。

然而,這並不表示,中國大陸已經默許民進黨的台獨立場。中國大陸之所以釋出善意,或許只是想說服民進黨,中國並非如他們想像得會帶給台灣威脅。經濟部次長 卓士昭表示 ,中國方面完全了解,我們在立法院正和對於服貿協議有所疑慮的人努力奮戰。但是目前看來,身為這場戰爭總司令的馬英九,似乎沒有幫上什麼忙。(吳凱琳譯)

Asia

Politics in Taiwan

Communal violence in India

North Korean posturing

Justice and vengeance in Bangladesh

Electricity in Japan

Banyan

China

The politics of dam-building

Learning to speak proper

Politics in Taiwan

Daggers drawn

A struggle between the president and a ruling-party heavyweight has consequences for the island’s relations with China

Daggers drawn 馬英九小刀出

- steeling, enameled steel tea kettles, kettle-cooke...

- acquiescence, quiescence,Australopithecus sediba,h...

“We can’t just muddle our way through this,” Mr Ma said on September 8th. That was two days after prosecutors alleged that Mr Wang had used his influence as the speaker of parliament in a court case. He had, they said, tried to persuade the justice minister, Tseng Yung-fu, to lobby prosecutors not to revive an embezzlement case against a prominent opposition lawmaker. Ker Chien-ming had been found guilty, but a higher court had overturned the verdict. Mr Ma said that Mr Wang’s alleged “influence-peddling” marked “the most shameful day in the history of democracy and rule of law in Taiwan”. On September 11th Mr Wang was expelled from the KMT.

In a country fed up with widespread corruption, Mr Ma might have expected applause. Yet he has conveyed the impression of caring more about flooring a political rival than upholding judicial independence. Meanwhile, Mr Wang’s protestations of innocence and his appeal as a soft-spoken, native-born politician (Mr Ma was born in Hong Kong of mainland Chinese parents) have earned him support across the political spectrum. On September 13th a court in Taipei, the capital, allowed Mr Wang to keep his party membership—and hence his position as speaker—while contesting the expulsion order. Unlike the justice minister, who resigned when the allegations were made public, Mr Wang is fighting.

Mr Ma is now in the humiliating position of having his legislative agenda handled by a man whom he has all but condemned as unfit for office. Worse, Mr Wang has long irritated the president by making concessions to opposition legislators over bills that Mr Ma, whose party has a small majority in the parliament, would prefer to ram through. An embittered Mr Wang is likely to be even less obliging. To add to the president’s embarrassment, other members of the KMT, including Lien Chan, the party’s honorary chairman, have criticised his handling of Mr Wang’s case. A senior colleague says the “general feeling” among KMT leaders is that Mr Ma acted hastily, having apparently failed to realise that Mr Wang might fight back in court.

The drama also has a Chinese dimension. Mr Ma’s frustration with Mr Wang had been growing even before prosecutors produced transcripts of secretly recorded telephone conversations appearing to show the speaker’s cosy relationship with Mr Ker, who is chief whip of the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Mr Ma had been eager for the parliament to give its approval to an agreement signed in June with China over the liberalisation of cross-strait trade and investment in services. The pact covers everything from banking to beauty parlours. Mr Wang had agreed to an opposition demand that sections of it be voted on in turn rather than as an entire package—an unprecedented approach in dealings with China. Taiwanese officials now fear delays and fresh rounds of haggling with China. They also worry about the reaction elsewhere. Taiwan’s chief trade negotiator, Cho Shih-Chao, says that if the island’s trading partners think that any agreement might unravel in the legislature, then “they might think again” about entering into free-trade talks.

The new trade pact may well encounter difficulties. DPP legislators are habitually wary of any deals with the mainland. They fear that China’s aim is to hasten its economic integration with Taiwan and use the influence it thereby gains to push the island into talks on reunification. Taiwanese officials say the agreement is more favourable to Taiwan than it is to China. They dismiss opposition claims that it will lead to a large influx of mainland migrants and threaten small Taiwanese businesses with unfair Chinese competition from deep-pocketed state-backed firms.

But even some KMT legislators have reservations about the pact, or at least what they see as Mr Ma’s weakness in talking up its merits. With Mr Ma’s popular support down to 9.2%, according to an opinion poll published on September 15th, these legislators worry more about their re-election prospects than offending the president. Mayoral elections will be held late next year. Parliamentary and presidential polls are due in January 2016.

China has expressed bafflement at the response in Taiwan to the trade deal. But it has avoided comment on the rift within the ruling party. It is likely to be deeply worried by both. A KMT split might facilitate a return to power by the DPP, which was helped into the presidency in 2000 by just such infighting. The following eight years of DPP rule were marked by tensions between Taiwan and China, which believed the party was trying to secure the island’s formal independence. Even under the KMT, future cross-strait deals are likely to be dissected by legislators in the same way as the services pact. The prospect of talks on a political settlement (urged by China but resisted in Taiwan even by Mr Ma) grows ever more remote.

Perhaps China is steeling itself for a possible DPP comeback (even though the party is hardly a model of unity itself). Since a visit to China in October 2012 by a former prime minister, Frank Hsieh Chang-ting, several DPP legislators and pro-DPP academics have been welcomed on the mainland, holding meetings with Chinese officials who once shunned them.

This does not mean acquiescence with the DPP’s independence-leaning stance, however. China, it appears, wants to persuade DPP politicians that the mainland is not as threatening as they think. “They realise what kind of war we are fighting” against free-trade sceptics in Taiwan’s parliament, says Mr Cho, the negotiator. Mr Ma, commander-in-chief of that war, has recently done his troops few favours.

沒有留言:

張貼留言