AN ALARMING assumption is taking hold in some quarters of both Beijing and Washington, DC. Within a few years, China’s economy will overtake America’s in size (on a purchasing-power basis, it is already on the cusp of doing so). Its armed forces, though still dwarfed by those of the United States, are growing fast in strength; in any war in East Asia, they would have the home advantage. Thus, some people have concluded, rivalry between China and America has become inevitable and will be followed by confrontation—even conflict.

Diplomacy’s task in the coming decades will be to ensure that such a catastrophe never takes place. The question is how?

Primacy inter pares

Some Western hawks see a China threat wherever they look: China’s state-owned businesses stealing a march in Africa; its government covering for autocrats in UN votes; its insatiable appetite for resources plundering the environment. Fortunately, there is scant evidence to support the idea of a global Chinese effort to upend the international order. China’s desires have an historical, even emotional, dimension. But in much of the world China seeks to work within existing norms, not to overturn them.

In Africa its business dealings are transactional and more often led by entrepreneurs than by the state. Elsewhere, a once-reactive diplomacy is growing more sophisticated—and helpful. China is the biggest contributor to peacekeeping missions among the UN Security Council’s permanent five, and it takes part in anti-piracy patrols off the Horn of Africa. In some areas China is working hard to lessen its environmental footprint, for instance through vast afforestation schemes and clean-coal technologies.

The big exception is in East and North-East Asia—one of the greatest concentrations of people, dynamism and wealth on Earth. There, both its rhetoric and its actions suggest that China is unhappy with Pax Americana. For centuries China lay at the centre of things, the sun around which other Asian kingdoms turned. First Western ravages in the middle of the 19th century and then China’s defeat by Japan at the end of it put paid to Chinese centrality. Today an American-led order in the western Pacific perpetuates the humiliation, in the eyes of Chinese leaders. Soon, they believe, their country will be rich and powerful enough to seize back primacy in East Asia.

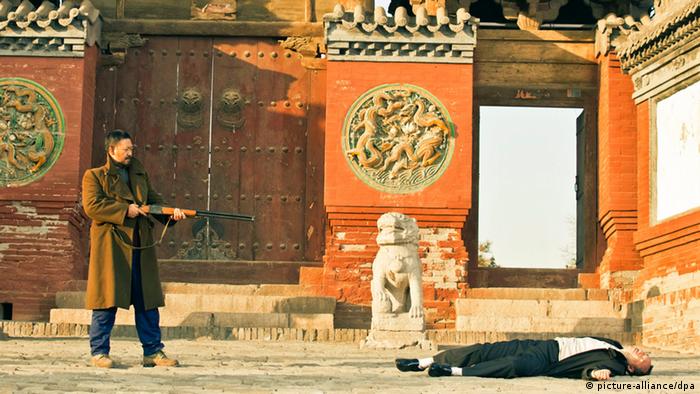

China’s sense of historical grievance explains a spate of recent belligerence. China has deployed ships and planes to contest Japan’s control of islands in the East China Sea, grabbed reefs claimed by the Philippines in the South China Sea and moved an oil rig into Vietnam’s claimed exclusive economic zone. All this has created alarm in the region. Some strategists say America can keep the peace only if it is firm in the face of Chinese expansionism. Others urge America to share power in East Asia before rivalries lead to a disaster.

America cannot walk away without grave consequences for the region and its own standing. Since the end of the second world war, American security has been the basis of Asian prosperity and an increasingly liberal order. It enabled Japan to rise from the ashes without alarming its neighbours. Indeed, China’s race to modernity could not have happened without it. Even Vietnam, America’s old foe, is clearer than ever that it wants America’s stabilising, reassuring presence.

Yet, if the liberal order is to survive, it must evolve. Denying the reality of China’s growing power would only encourage China to reject the world as it is. By contrast, if China can prosper within the system, it will reinforce it. That is why the United States needs to acknowledge one increasingly awkward aspect of its leadership: American advantage is hard-wired into the system in ways that a rising power might justifiably resent.

For a great power to find a new equilibrium with an emerging one is hard—because every adaptation looks like a retreat. Three principles should guide America.

First, it should only make promises that it is prepared to keep. On the one hand, America would be foolish to draw red lines around specks of reef in the South China Sea. On the other, if America is to count for anything, its allies need to know that they can depend on it. Although Taiwan is central to China’s sense of its own honour, America should leave Beijing in no doubt that it would come to the island’s defence.

Second, even in security, America must make room. China’s participation in America’s recent RIMPAC naval exercises off Hawaii was a start. China could be invited to join Asian exercises, including for disaster relief. And America should avoid a cold-war battle for the loyalty of regional powers.

Lastly, America will find it easier to include China in new projects than to give ground on old ones—and should make more effort to do so. It is nonsensical that America should be leading the formation of the region’s biggest free-trade area, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, without the inclusion of the region’s largest economy. And there is no reason to exclude China from co-operation in space. Even during the cold war American and Soviet astronauts worked together.

Let the dragon in

Why should China be satisfied with a bit more engagement when primacy is what it seeks? There is no guarantee that it will be. Just now the rhetoric coming out of Beijing is full of cold-war, Manichean imagery. Yet sensible Chinese understand that their country faces constraints—China needs Western markets, its neighbours are unwilling to accept its regional writ and for many more years the United States will be strong enough militarily and diplomatically to block it. And in the longer run, the hope is that the Chinese system will of itself adapt from one-party rule to some more liberal polity that, by its nature, is more comfortable with the world as it now is.

Drawing China into a strengthened regional framework would not be to cede primacy to it. Nor would it be to abandon a liberal order that has served Asia—and America—so well. It may, in the end, not work. But given the huge dangers of rivalry, it is essential now to try.