Wary of Future, Professionals Leave China in Record Numbers

Lee Yangang and his wife, Wang Lu, emigrated to Sydney, Australia, from Beijing last year, saying they felt insecure in China.

By IAN JOHNSON

Published: October 31, 2012

BEIJING — At 30, Chen Kuo had what many Chinese dream of: her own

apartment and a well-paying job at a multinational corporation. But in

mid-October, Ms. Chen boarded a midnight flight for Australia to begin a

new life with no sure prospects.

Connect With Us on Twitter

Follow @nytimesworld for international breaking news and headlines.

Sim Chi Yin for The New York Times

Chen Kuo, 30, in Beijing just before she left for Australia.

Like hundreds of thousands of Chinese who leave each year, she was

driven by an overriding sense that she could do better outside China.

Despite China’s tremendous economic successes in recent years, she was

lured by Australia’s healthier environment, robust social services and

the freedom to start a family in a country that guarantees religious

freedoms.

“It’s very stressful in China — sometimes I was working 128 hours a week

for my auditing company,” Ms. Chen said in her Beijing apartment a few

hours before leaving. “And it will be easier raising my children as

Christians abroad. It is more free in Australia.”

As China’s Communist Party prepares a momentous leadership change in

early November, it is losing skilled professionals like Ms. Chen in

record numbers. In 2010, the last year for which complete statistics are

available, 508,000 Chinese left for the 34 developed countries that

make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. That is a 45 percent increase over 2000.

Individual countries report the trend continuing. In 2011, the United

States received 87,000 permanent residents from China, up from 70,000

the year before. Chinese immigrants are driving real estate booms in

places as varied as Midtown Manhattan, where some enterprising agents

are learning Mandarin, to the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, which

offers a route to a European Union passport.

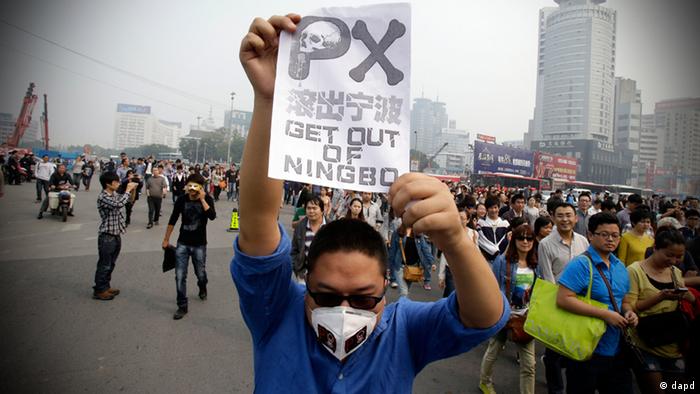

Few emigrants from China cite politics, but it underlies many of their

concerns. They talk about a development-at-all-costs strategy that has

ruined the environment, as well as a deteriorating social and moral

fabric that makes China feel like a chillier place than when they were

growing up. Over all, there is a sense that despite all the gains in

recent decades, China’s political and social trajectory is still highly

uncertain.

“People who are middle class in China don’t feel secure for their future

and especially for their children’s future,” said Cao Cong, an

associate professor at the University of Nottingham who has studied

Chinese migration. “They don’t think the political situation is stable.”

Most migrants seem to see a foreign passport as insurance against the

worst-case scenario rather than as a complete abandonment of China.

A manager based in Shanghai at an engineering company, who asked not to

be named, said he invested earlier this year in a New York City real

estate project in hopes of eventually securing a green card. A

sharp-tongued blogger on current events as well, he said he has been

visited by local public security officials, hastening his desire for a

United States passport.

“A green card is a feeling of safety,” the manager said. “The system

here isn’t stable and you don’t know what’s going to happen next. I want

to see how things turn out here over the next few years.”

Political turmoil has reinforced this feeling. Since early this year, the country has been shocked by revelations that Bo Xilai, one of the Communist Party’s most senior leaders, ran a fief that by official accounts engaged in murder, torture and corruption.

“There continues to be a lot of uncertainty and risk, even at the

highest level — even at the Bo Xilai level,” said Liang Zai, a migration

expert at the University at Albany. “People wonder what’s going to

happen two, three years down the road.”

The sense of uncertainty affects poorer Chinese, too. According to the

Chinese Ministry of Commerce, 800,000 Chinese were working abroad at the

end of last year, versus 60,000 in 1990. Many are in small-scale

businesses — taxi driving, fishing or farming — and worried that their

class has missed out on China’s 30-year boom. Even though hundreds of

millions of Chinese have been lifted from poverty during this period,

the rich-poor gap in China is among the world’s widest and the economy

is increasingly dominated by large corporations, many of them state-run.

“It’s driven by a fear of losing out in China,” said Biao Xiang, a

demographer at Oxford University. “Going abroad has become a kind of

gambling that may bring you some opportunities.”

Zhang Ling, the owner of a restaurant in the coastal city of Wenzhou, is

one such worrier. His extended family of farmers and tradesmen pooled

its money to send his son to high school in Vancouver, Canada. The

family hopes he will get into a Canadian university and one day gain

permanent residency, perhaps allowing them all to move overseas. “It’s

like a chair with different legs,” Mr. Zhang said. “We want one leg in

Canada just in case a leg breaks here.”

Emigration today is different from in past decades. In the 1980s,

students began going abroad, many of them staying when Western countries

offered them residency after the 1989 Tiananmen Square uprising. In the

1990s, poor Chinese migrants captured international attention by paying

“snakeheads” to take them to the West, sometimes on cargo ships like

the Golden Venture that ran aground off New York City in 1993.

Now, years of prosperity mean that millions of people have the means to

emigrate legally, either through investment programs or by sending an

offspring abroad to study in hopes of securing a long-term foothold.

Wang Ruijin, a secretary at a Beijing media company, said she and her

husband were pushing their 23-year-old daughter to apply for graduate

school in New Zealand, hoping she can stay and open the door for the

family. They do not think she will get a scholarship, Ms. Wang said, so

the family is borrowing money as a kind of long-term investment.

“We don’t feel that China is suitable for people like us,” Ms. Wang

said. “To get ahead here you have to be corrupt or have connections; we

prefer a stable life.”

Perhaps signaling that the government is concerned, the topic has been

extensively debated in the official media. Fang Zhulan, a professor at

Renmin University in Beijing, wrote in the semiofficial magazine

People’s Forum that many people were “voting with their feet,” calling

the exodus “a negative comment by entrepreneurs upon the protection and

realization of their rights in the current system.”

The movement is not all one way. With economies stagnant in the West and

job opportunities limited, the number of students returning to China

was up 40 percent in 2011 compared with the previous year. The

government has also established high-profile programs to lure back

Chinese scientists and academics by temporarily offering various perks

and privileges. Professor Cao from Nottingham, however, says these

programs have achieved less than advertised.

“Returnees can see that they will become ordinary Chinese after five

years and be in the same bad situation as their colleagues” already in

China, he said. “That means that few are attracted to stay for the long

run.”

Many experts on migration say the numbers are in line with other

countries’ experiences in the past. Taiwan and South Korea experienced

huge outflows of people to the United States and other countries in the

1960s and ’70s, even as their economies were taking off. Wealth and

better education created more opportunities to go abroad and many did —

then, as now in China, in part because of concerns about political

oppression.

While those countries eventually prospered and embraced open societies,

the question for many Chinese is whether the faction-ridden incoming

leadership team of Xi Jinping, chosen behind closed doors, can take

China to the next stage of political and economic advancement.

“I’m excited to be here but I’m puzzled about the development path,”

said Bruce Peng, who earned a master’s degree last year at Harvard and

now runs a consulting company, Ivy Magna, in Beijing. Mr. Peng is

staying in China for now, but he says many of his 100 clients have a

foreign passport or would like one. Most own or manage small- and

medium-size businesses, which have been squeezed by the policies

favoring state enterprises.

“Sometimes your own property and company situation can be very

complicated,” Mr. Peng said. “Some people might want to live in a more

transparent and democratic society.”

日本政府本週在國內媒體上發起廣告攻勢﹐

日本政府本週在國內媒體上發起廣告攻勢﹐

人口老龄化和劳动大军萎缩有朝一日将使“世界工厂”成为过去

人口老龄化和劳动大军萎缩有朝一日将使“世界工厂”成为过去